An Energy Cooperative is Reshaping Power in Puerto Rico’s Central Mountains

The group's mission is to reactivate abandoned hydroelectric power plants in Puerto Rico's mountainous interior, but in the short term it operates two microgrids

Maribel Hernandez Soto’s family has worked in the energy sector in Puerto Rico for three generations. Her grandfather was involved with the electrification of the archipelago around the beginning of the 20th century, when hydropower emerged as a viable energy source, because of Puerto Rico's abundant rivers and mountainous terrain. Several hydroelectric power plants were built across the archipelago, four of which Maribel’s father worked at during his career.

By the 1960s, Puerto Rico began shifting away from hydropower and other energy sources in favor of cheap imported oil. The move left the archipelago vulnerable to volatile oil prices over the decades. The archipelago cemented its dependence on fossil fuels with the opening of the Costa Sur and Aguirre oil-burning plants in 1962 and 1975, respectively, followed by a coal plant in 2002.

Now, Hernandez Soto is continuing her family’s energy legacy as Community Coordinator of La Cooperativa Hidroeléctrica de la Montaña (CHM). It’s a hands-on role that keeps her busy. On a sunny day in the remote mountain town of Castañer, she was approached by several locals wanting to chat and received numerous calls from others.

“It was very difficult because we were the first co-op,” Hernandez Soto says. “We had to open the way for the other co-ops.” In addition to the challenge of pioneering on this front, CHM—which relies heavily on federal funding—is now facing growing financial uncertainty as President Donald Trump's administration continues to make budget cuts.

%20team%20members%20inspect%20a%20fuse%20box.jpg)

CHM was initially founded to revive long-neglected hydroelectric power plants in Puerto Rico’s mountainous interior, about a two-hour drive from the capital. While that goal remains, the group shifted to a more attainable short-term mission to expand solar access in Puerto Rico’s central region.

Power outages are common, partly because most electricity is generated on the southern coast and must travel through a fragile transmission network to reach the more populous areas of the archipelago. These issues have contributed to Puerto Rico’s electricity being the fourth most expensive on average when compared to the 50 states.

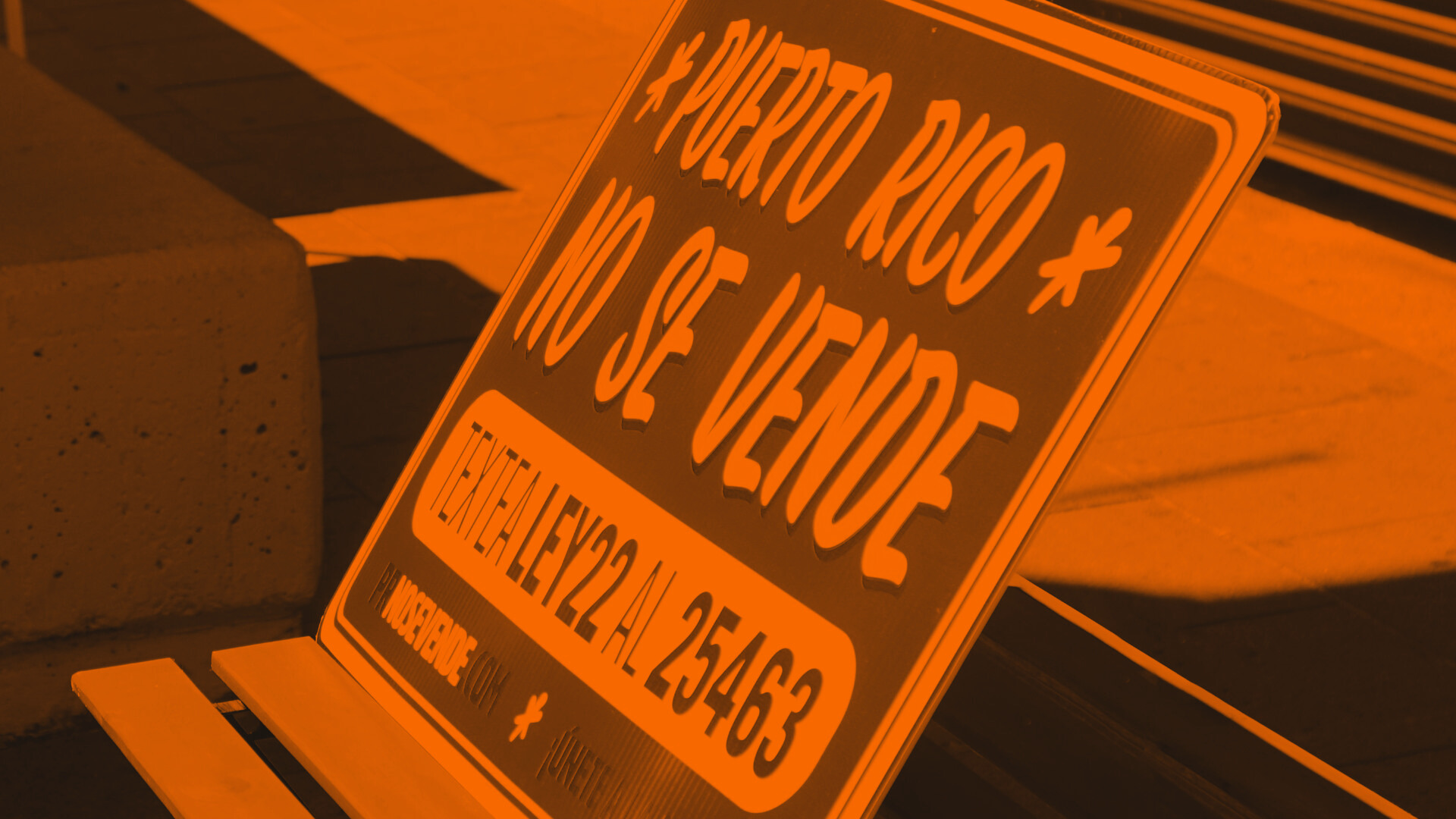

One emerging solution could be energy cooperatives like CHM, member-owned nonprofit organizations that generate and distribute electricity independent of the main grid with a focus on affordability and reliability. Puerto Rico legislated for such cooperatives in 2018 and CHM formed the following year, reportedly becoming the archipelago’s first energy cooperative.

Today, there are 13 people on the cooperative’s team. Seven serve as ambassadors for the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Solar Access Program, which provides solar systems for low-income households in Puerto Rico. In the year from February 2024 to February 2025, the team handled around 3,000 applications for the program, of which about 2,400 were successful.

Community Microgrids

CHM is also working to expand solar energy access through its Resiliencia Energética Fotovoltaica Comunitaria (ReEnFoCo) project, which develops solar-powered microgrids to supply energy locally even when the main grid fails.

Two microgrids have been created under ReEnFoCo so far. The three-year-old project prioritizes local businesses that can use solar energy during sunlight hours without relying heavily on expensive battery storage that is used mainly during emergencies. Residential properties, which usually reach peak energy demand at night, remain a longer-term goal.

Under CHM’s model, microgrid users are owner-partners. “Everyone has a voice in how it is run,” Ben Tremblay says. He is a CHM project engineer and an energy innovator fellow through a DOE program that places professionals with energy organizations.

One condition of joining the microgrid is that participants must allow the community to use their electricity during outages. That means locals can refrigerate medicines, charge electronic devices and administer electric-dependent medical treatments like dialysis.

One of CHM’s pilot microgrids in Castañer supports a barbershop, beauty salon, post office, apartment, house and a former ice cream parlor set to reopen soon as another business. Hernandez Soto says the microgrid was the only one in Puerto Rico that worked before, during and after Hurricane Fiona in 2022, thanks to its batteries that store two to three days’ worth of electricity.

The batteries are located in the back room of Juny's barbershop, one of the businesses benefitting from the microgrid, which is owned by Alfonso "Juny" Arroyo. Originally from the area, he wears a jersey that reads “support local business” and features logos of some Castañer establishments.

Arroyo got involved with the microgrid through Hernandez Soto and is now trained to respond to energy issues that may arise. “He helped us a lot,” Hernandez Soto says with a smile. “Now he’s a barber, but maybe in five years he’s going to be an installer!,” she jokes.

Arroyo says his electricity bill has dropped dramatically. He used to pay $100 per month for electricity from the main LUMA grid, but now pays the minimum $4 connection fee.

For now, microgrid users receive electricity for free, but in December, 2024 the Puerto Rico Energy Bureau approved CHM’s energy rate—which remains confidential. That rate will not exceed what LUMA charges. “We think it’s going to be much lower,” Tremblay says. “That’s the mission of the cooperative: to provide cost-effective, resilient energy from renewable sources.”

CHM relies on federal funding, primarily from the DOE and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). However, those relationships have grown more uncertain since the new federal administration took office in January 2025. “Things keep changing every week,” Tremblay says. “Communication with all the federal agencies we interact with—the DOE, the USDA—has been very difficult.”

CHM has plans for 128 more microgrids under ReEnFoCo. That expansion is reliant on federal funding, which is now in question given the Trump administration’s energy policy. “All this is very dependent on what happens in the next few months,” Tremblay says. While CHM is researching alternative funding sources, he admits that its work “is very hard to do without federal funding.”

The cooperative was close to signing a $47 million USDA loan under the Powering Affordable Clean Energy (PACE) program, but the process stalled after the new federal administration was sworn in. On March 25, the USDA announced it would release previously approved funds if grantees revise applications to reflect the administration’s energy priorities to “remove harmful DEIA and far-left climate features”. While CHM's loan agreement has not been signed (and isn’t directly affected by this announcement), its team members hope that the cooperative will be able to proceed soon.

Hydropower’s Promise

CHM still sees a future for hydropower, which was the initial focus of the cooperative when it was established. As Puerto Rico struggles with the cost and pollution of fossil fuels, CHM believes a renewed focus on hydropower could offer clean and affordable electricity.

CHM’s Hidroenergía Renace (Hydro Energy Reborn) project aims to rehabilitate the Caonillas and Dos Bocas hydroelectric power plants in the municipalities of Utuado and Arecibo, respectively. The Caonillas plants currently aren’t operational, while the Dos Bocas plant generates approximately 6 megawatts of electricity. If run continuously, this is enough to supply electricity to 3,000 to 6,000 homes, depending on the time of year, energy demand, location and other factors.

CHM wants to raise the combined output of the three hydroelectric power plants to 50 megawatts—the estimated generative capacity of the plants after improvements and maintenance. “It’d be enough for the whole center of the island,” Hernandez Soto says.

In September 2023, the Puerto Rico Energy Bureau (PREB) approved nearly $320.8 million in funding under the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority’s (PREPA) 10-year infrastructure plan from 2020 to upgrade 16 hydraulic power plants, including Dos Bocas as well as the two in Caonillas, but progress has been slow.

A hydroelectric power plant stores water in a dam and then releases it through turbines to generate electricity before the water flows back into the river. Over its lifetime, the greenhouse gas emissions intensity of a hydroelectric power plant is less than 3% of a coal plant. In 2024, however, 7.6% of Puerto Rico’s electricity came from coal while hydroelectricity contributed just 1.8%. Meanwhile, 23.2% of the archipelago’s electricity came from natural gas and 62.4% of it was generated by petroleum.

Hydropower could also reduce Puerto Rico’s reliance on imported fossil fuels, according to Rachael Kohler, another CHM project engineer and DOE energy innovator fellow. “It would give power back to the center of the island, which is often overlooked in favor of the metropolitan area.”

In 2019, Puerto Rico’s Public-Private Partnerships Authority began exploring the rehabilitation of the archipelago’s state-owned hydroelectric power plants. CHM led a consortium that submitted a proposal to manage the plants, but the process was terminated in 2023. Kohler says the decision was partly attributed to concerns that community groups lack the technical capacity to manage hydro facilities, which require more expertise than the solar projects they have successfully implemented across Puerto Rico.

“It’s a valid concern,” Kohler says. “But they’re not really doing anything either. So are you going to take a little bit of a chance or are you just going to continue to let them deteriorate?”

Kohler acknowledges that hydroelectric power plants often require significant maintenance after storms, when sediment can clog dams and reduce their generative capacity. “Sometimes they’re not even producing usable electricity,” Kohler says. “It just kind of stabilizes the electricity system.” That stabilizing effect is known as reactive power, which helps keep voltage steady across the grid, much like a water pump maintains pressure in a plumbing system.

A Long-term Vision

Kohler’s “favorite” project is Microrred de la Montaña (Microgrid of the Mountain), CHM’s long-term vision to link the ReEnFoCo microgrids with the hydroelectric power plants to form an inter-municipal grid in the island’s central region. A control center would manage the grid and could prioritize critical facilities like the local hospital in Castañer, the last medical institution in Puerto Rico to regain power after Hurricane María in 2017. The goal is a regional grid that provides reliable, affordable and renewable electricity to the community. “There’s a lot of potential,” Kohler says.

Despite the challenges CHM has faced since its establishment in 2019, the team ultimately remains driven and hopeful in part because of its success to date. “People believe in our mission, including people in government offices,” Kohler says. “So at the end of the day, it’s just convincing them to help us.”

Under the shade of a tree in the main square in Castañer, Hernandez Soto acknowledges the difficulties, but shares a sense of optimism. “There’s uncertainty,” she says when speaking about one of CHM’s initiatives. “But we still have faith.”