How Community Cinema Creates More Inclusive Stories in Puerto Rico

A queer film production company, a grassroots organization, and an academic laboratory in Puerto Rico share participatory practices for community filmmaking

Filmes Casa’s production plans changed unexpectedly during the filming of the fifth Hustleween, a ball to celebrate and raise funds for transmasculine people in Puerto Rico. They would have only one shooting day instead of two. The production team called for the cameras to be turned off after 10 hours of documenting the event organized by transfeminist network Espicy Nipples. Prioritizing work-time limits is one of the practices Filmes Casa has adopted to create a healthy environment in the film industry. However, the crew was so motivated they kept on recording. To top off the long day, they even joined in the dancing.

Simple practices such as including the production team in a film’s planning and providing spaces for them to voice their opinions are atypical in traditional productions. "Sometimes, you're 12 hours in a place where you never spoke because there's no space for you; for you to speak," said Yarelmi Iglesias Vázquez, who worked as the sound engineer for Hustleween, and asked to be identified only as Yare going forward. This focus on participatory processes is fundamental in community filmmaking, a film practice that amplifies forgotten and silenced voices.

In Hustleween, Filmes Casa highlighted queer stories beyond trauma and suffering. "Everyone had the intention to work from a different perspective; from the reality that, yes, we are hurting, but we also feel joy and euphoria, in contrast to all the dysphoria we can feel in other spaces," Yare expressed in a video call. The short film, full of dance, music, and a runway, won the audience award at festivals in New York and Puerto Rico. Yarelmi recalled screenings where the audience enjoyed the documentary, because "we were also feeling that euphoria while making the project."

Yare represented Filmes Casa at the First Gathering on Community Cinema in Puerto Rico, held at the beginning of 2025, at the Cine Solar of Casa Pueblo (Adjuntas), a community-managed project known worldwide for its advocacy for environmental justice, which also opened a Solar Cinema shortly after the pandemic. There, filmmakers, academics, and members of grassroots organizations reinforced the need to support community cinema to repair and grow the visibility of stories excluded from official and institutional narratives.

The reflections of 20 organizations and over 30 participants were integrated into a report, which sheds light on this practice in the Caribbean.

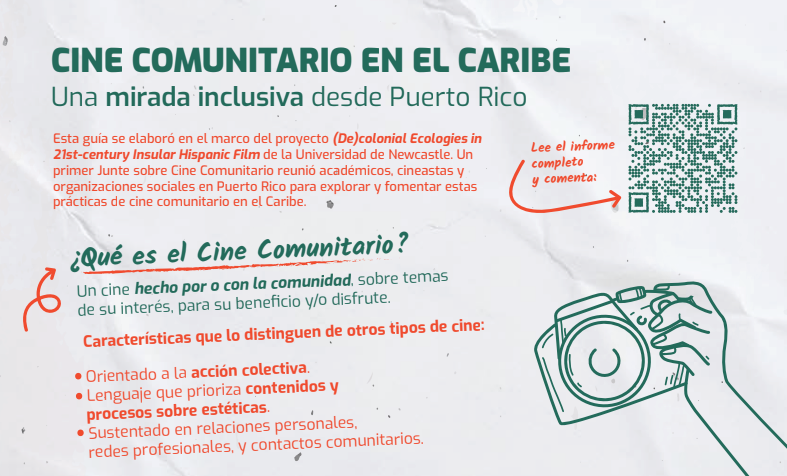

What is Community Cinema?

Community cinema is born from the need to communicate without intermediaries, according to the Bolivian writer, filmmaker, and journalist Alfonso Gumicio Dagrón. A report produced as part of the project "(De)colonial Ecologies in 21st-century insular Hispanic Film" by Newcastle University (England), summarizes it as "a cinema made by or with the community, about topics of interest to the community, and for the benefit and/or enjoyment of the community." The project analyzes and compares films from the Greater Antilles that highlight social and environmental justice and how they are affected by colonialism.

The investigation expands the original concept of community cinema to include collaborations between community members and audiovisual professionals, non-governmental organizations, professional associations, and university research laboratories. The document drew on the different variants of community cinema discussed at the meeting facilitated by researchers Dunja Fehimović and Cecilia Sosa. It also examines how community cinema can bring about positive change.

The report on community cinema in Puerto Rico is open to comments, with the aim of continuing to expand the conversation with communities and filmmakers, to foster these practices.

"If we don't do it, no one will"

Communities that have been structurally marginalized must be autonomous. "We have to take care of everything ourselves." The multidisciplinary artist Hery Colón Zayas reflected that this applies to filmmaking as well as public health issues and environmental contamination. Colón Zayas was born in Aguirre, Salinas— a town in Puerto Rico’s southern region. He is co-founder of Casa Comunitaria de Medios, an organization that started producing community films in that town, and has expanded to manage an art gallery, offer historical tours, and hold cultural gatherings. Through all these techniques, they rescue and share their stories with the goal of "building life from there."

The group has seen that creating non-hierarchical dialogue spaces has been vital for people to value their own history. Colón Zayas explains that it is a challenge to convince his peers that "their history is just as important as that of the four Bostonians who migrated to establish the community," referring to the landowners who founded Aguirre as a company town.

Casa Comunitaria de Medios uses video profiles as a tool to rescue these community stories. The production process is just as important as the story itself, said Colón Zayas. He gave the example of how Wendy León Vázquez —or "Lula," as she is known in the neighborhood— agreed to the interview after several everyday encounters in which he emphasized the importance of telling her story. After recording the interview, they showed her the first cuts so she could provide her input during the editing process. When they asked for footage of her father, they explained why they wanted to show him and did not demand specific formats.

"These are your memories. We are going to adjust it to what we have, because this is your space. This is your video. This is your story," stated Colón Zayas.

The challenge, shared among many grassroot movements, is scarcity: not owning one's own time. "The space to meet up is limited because there is instability, for example, for working people; there is an uncertainty about when you have work and when you don't," acknowledged the rapper, who lives in a town where jobs are scarce, forcing people to move to different places. However, the lack of resources hasn’t stopped him or Casa Comunitaria from experimenting.

Creating Models and Sharing Learnings

In addition to production houses and community-based groups, community filmmaking practices shared during the gathering also include academically based research projects located in university institutions. An example of this is the Oral History Laboratory at the Mayagüez University Campus of the University of Puerto Rico, directed by Ricia Anne Chansky and Jaquelina E. Álvarez.

The laboratory began after Hurricane Maria, in 2017, with an optional assignment for students to process their experiences. "Each of the students handed in their assignment on paper written with a pencil or pen because there was no electricity, and I read them by candlelight," Chansky recalled. That inspired her to start an oral history project documenting the aftermath of the environmental and political crisis.

"Everything that Jackie and I do is rooted in the classroom and rooted in providing opportunities for our students to feel as though they have agency, to understand that their voice matters, to understand that when they conduct an interview and it's preserved in the library or becomes part of a film, they are building change," explained Chansky, who is an English professor.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, both professors obtained a grant that allowed them to formalize the laboratory to continue documenting and preserving stories. The work, Álvarez said, promotes the autonomy of those whose stories are being documented, unlike institutional mediators who traditionally decide how stories are preserved and presented in libraries or archives.

"We respect the way that people want to be named or if they want to be anonymous, but also that persons in the future change their mind. Following the decolonial practices, the narration is owned by the person that tells the story. So we will respect the wishes of that interviewee," explained Álvarez.

However, a participatory production model comes with the challenge of balancing the times of the university, funders, and the community. Chansky and Alvarez have learned, for example, that it is beneficial to give their collaborators references and examples of how the laboratory can contribute to their community.

The laboratory's mission is for these experiences to become a model of non-extractive production and research. For this reason, it shares strategies through presentations and publications. Among the tools they have developed is “An Ethical Framework for Interviewing in the Aftermath of a Disaster”.

The people interviewed for this story agreed on the need to share learnings to sustain community filmmaking long-term. As self-taught individuals, Colón Zayas and Yare have learned from their own experience. Acquiring these techniques and expertise has cost them much time and effort, so they share the desire to lower the entry barriers for others to record their own stories.

“I aspire to continue sharing and creating these spaces where people can gather to be creative, learn, and take away tools they can use. For me, that is community filmmaking. We build community in the process,” concluded Yare.

What began as the First Gathering on Community Cinema in Puerto Rico intends to expand to the rest of the Caribbean. Researchers Fehimović and Sosa stated in the report that “the sustainability of community cinema does not depend exclusively on funding,” as its strength is linked to networks and potential collaborators at the local and regional levels.

More than a production framework, community cinema allows us to envision a more just country; a healthier and more prosperous society. "They took away our possibility to dream, and I believe that being able to dream is the first thing that will motivate us to imagine something [different]," reflected Colón Zayas.

This article was produced in collaboration with Newcastle University, with funds from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) of the United Kingdom.